Hey all! Today I’m going to take up a cause and champion it! Hoorah!

BUT FIRST: two rather exciting annoucements.

The first is that I’ve had my short story, “Alpirsbach,” published in the most recent issue of Cobalt. I’m incredibly excited and grateful; that story is very close to my heart. Go read it! It’s super short, I promise it won’t take long. 🙂

The second is that this blog–yes, this very same one you’re reading right now–is 3 years old! HAPPY BIRTHDAY AMPERSAND! I think you’re getting better with age. (She says not at all self-servingly).

On Ampersand’s first birthday, I did a brief history of its namesake. (I’ve always championed it as my favorite punctuation mark, but if I’m truly, brutally honest, I think I actually prefer the semicolon. Ask me about it later).

Some recent posts I’ve been proud of: Play it Again, my attempt to corral my thoughts about what music school taught me about writing and life; Song of the Earth, a roundup of music generated by the planet; and Playing Tricks on Me, an attempt to visually describe what the world looked like when I got my pupils dilated (I know that sounds lame, I know it does, but I think it’s actually pretty cool). So maybe check those out if you’re new here!

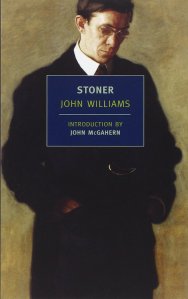

BUT TODAY. Oh, today. Today I’m going to tell you to read something. And that something is this:

Stoner is a small, forgotten novel by John Williams which was given to me at Christmas by a friend. It was unassuming, not flashy; I read the summary and wasn’t dazzled. But it turned out to be one of the most beautiful reading experiences I’ve had in a long time.

Stoner is a small, forgotten novel by John Williams which was given to me at Christmas by a friend. It was unassuming, not flashy; I read the summary and wasn’t dazzled. But it turned out to be one of the most beautiful reading experiences I’ve had in a long time.

It has a simple premise: this is the story of William Stoner, a man who was a professor of literature in the 1920s and 30s. He comes from a farming family in Missouri, he goes to school, he gets married, he has a daughter, he is stymied professionally and at home, he has an affair, he has to end it, and years later he dies.

But Williams imbues the world with so much clarity and beauty, ties everything together with such precision, that somehow this ordinary life is transformed and elevated into a beacon of humanity and integrity. It’s astonishing. I’m reminded of a quote I read in a recent New York Times article by David Brooks, “The Moral Bucket List.” (I know, it’s kind of a bad title. But a good read! He talks about wanting to live with a generosity of spirit and depth of character). But here’s the quote, about living as a “stumbler”, a person who “faces her imperfect nature with unvarnished honesty,with the opposite of squeamishness. Recognizing her limitations, the stumbler at least has a serious foe to overcome and transcend.”:

“The stumbler doesn’t build her life by being better than others, but by being better than she used to be. Unexpectedly, there are transcendent moments of deep tranquility. For most of their lives their inner and outer ambitions are strong and in balance. But eventually, at moments of rare joy, career ambitions pause, the ego rests, the stumbler looks out at a picnic or dinner or a valley and is overwhelmed by a feeling of limitless gratitude, and an acceptance of the fact that life has treated her much better than she deserves.”

Now, Stoner is constantly thwarted. His life does not treat him better than he deserves; in fact, life screws him. But Williams still manages to convey this incidental transcendence within a life made small by the people around him. Moments of Stoner’s life are gifted with rare beauty; does this balance out the overall disappointment of what he’s accrued? I don’t know. Probably not. But this book just hit me right in the heart.

I went through and tried to decide what excerpts and quotes were most effecting in trying to convey its effect, but in the end I decided on two longish sections from the very very end of the novel, as Stoner lays dying.

Dispassionately, reasonably, he contemplated the failure that his life must appear to be. He had wanted friendship and the closeness of friendship that might hold him in the race of mankind; he had had two friends, one of whom had died senselessly before he was known, the other of whom had now withdrawn so distantly into the ranks of the living that….He had wanted the singleness and the still connective passion of marriage; he had had that, too, and he had not know what to do with it, and it had died. He had wanted love, and he had had love, and had relinquished it, had to let it go into the chaos of potentiality. Katherine, he thought. “Katherine.”

And he had wanted to be a teacher, and he had become one; yet he knew, he had always known, that for most of his life he had been an indifferent one. He had dreamed of a kind of integrity, of a kind of purity that was entire; he had found compromise and the assaulting diversion of triviality. He had conceived wisdom, and at the end of the long years he had found ignorance. And what else? he thought. What else?

What did you expect? he asked himself.

He heard the distant sound of laughter, and he turned his head toward its source. A group of students had cut across his back-yard lawn; they were hurrying somewhere. He saw them distinctly; there were three couples. The girl were long-limbed and graceful in their light summer dresses, and the boys were looking at them with a joyous and bemused wonder. They walked lightly upon the grass, hardly touching it, leaving no trace of where they had been. He watched them as they went out of his sight, where he could not see; and for a long time after they had vanished the sound of their laughter came to him, far and unknowing in the quiet of the summer afternoon.

What did you expect? he thought again.

A kind of joy came upon him, as if borne in on a summer breeze. He dimly recalled that he had been thinking of failure–as if it mattered. It seemed to him now that such thoughts were mean, unworthy of what his life had been. Dim presences gathered at the edge of his consciousness; he could not see them, but he knew that they were there, fathering their forces toward a kind of palpability he could not see or hear. He was approaching them, he knew; but there was no need to hurry. He could ignore them if he wished; he had all the time there was.

There was a softness around him, and a languor crept upon his limbs. A sense of his own identity came upon him with a sudden force, and he felt the power of it. He was himself, and he knew what he had been.

Stoner gets written up from time to time, (here are two recent examples), always with headlines like “The Greatest American Novel You’ve Never Heard Of”, or something like that. Well, now you’ve heard of it.

Please tell me: what’s something else I’ve never heard of? I want to read it all.