In honor of the newly-blown spring that is surely just around the corner, I’m writing today about literary perennials, those constants we couldn’t do without, the volumes that get read and reread and kept close to us no matter what.

When I moved from New York to Ohio recently, I had to put about 98% of my library in storage. I went through my books carefully, making mostly sage but sometimes rash decisions about what I would need with me. I held each book, thought, “will I miss this for the next 6 months to a year?” and boxed them accordingly.

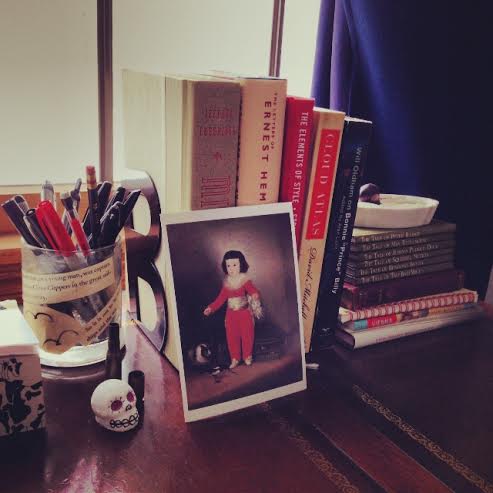

Of the “I will miss them so terribly I can’t bear to be parted from them” box, there are some that are so important to me they can’t even live on the shelf. Following are some pictures I’ve taken from my desk over the past few months.

I don’t know if you could see, but there are certain titles that never leave the desk; while I do keep my “books in waiting” there as well, The Elements of Style (Strunk and White), The Letters of Ernest Hemingway, Volume II (1923-1925), Will Oldham on Bonnie “Prince” Billy, selected books by Beatrix Potter, and Jane Eyre are always immediately to hand, along with a book of maps of Vienna, just because.

Why? Oh, different reasons. The Elements of Style for any sudden questions of grammar or formatting, Hemingway’s letters because I find the story of his early struggles inspirational (living above a sawmill, able to afford no entertainment other than long walks, writing in a cold garret, and above all his quest for truth and style) and comforting. If a Great Writer once felt as I do, as insecure and unsure, then maybe, just maybe, there’s hope for me yet.

Beatrix Potter because those were the stories I first loved and understood on the level of “a story.” Also they’re cute. Jane Eyre because I reread it every year and now I have a beautiful early edition…I have a different relationship with Jane every time I go through that novel. (I wrote a little bit about my love for that novel in an earlier post).

And Will Oldham on Bonnie “Prince” Billy, a book-length interview edited by Alan Licht, because reading his views on art, creativity, and productivity are like taking the hand of someone familiar. My copy is beaten up and signed by the artist; I can dip into it at random and always pull up something I needed to read in that moment. Stuff like:

Q: Do you think a song is every really finished?

A: I feel like a song is completed when the writing is done and I present it to a friend, partner, or group of musicians. Then it’s completed when we record together and finish mixing. Then it’s completed each and every time someone listens. I think that a song, for the most part, is completed by the listening experience. It enters in people’s brains and mutates and then might get completed again–in their dreams, in mix tapes that they make, or in new listening experiences that they have. So it isn’t ever finished because there’s never going to be a definitive listening experience.

and

Q: Overall, what effect do you think the audience has on your work?

A: I feel the value of my work is determined very precisely by the audience. What does entertainment mean, anyway, and what’s the difference between that and art? I would say the main difference is that art isn’t necessarily funded by the consumer, but entertainment always is. In that way, entertainment is a million times more important to me than art, and being an entertainer is more important to me than being an artist. The relationship with the audience is so direct, while the government or rich collectors are going to pay for something that is art rather than the person who is actually going to have a relationship with the piece. That’s what’s most important to me about what I do. I think of entertainment as being very serious and important, from Laurel and Hardy upward. It has to do with emotions of release, giving up, or extreme hilarity and absurdity.

It’s rewarding when I find a broader audience that doesn’t think I’m too crazy. [I’m] trying to make something for that audience to experience, also knowing that at some level I will be sharing the experience. My absolute, purest particular taste would not be something that could be appreciated on a grand scale. It just wouldn’t. If I really made a record just to serve myself I would end up in a dark, wet room, you know? That’s not really where I want to be. That’s why it’s more important to me to make a record that serves itself and its audience well. A good record should involve my needs, the listeners’ needs, and the needs of the other people who worked on the record. If I manage that, I feel I’ve accomplished something; but ultimately it is the audience that holds the lion’s share of determining if a record is worthwhile. The only way for my entire audience to appreciate the music is if they come to it of their own accord and find something in it that satisfies them as individuals. I’ll do what I do, and they’ll do what they do, and hopefully a mutual understanding can be formed.

One thing I value about him as a musician and a performer is the depth of thought which goes into each presentation of and interaction with his work. It creates music that can stand up to (and rewards) close listening, repeat listening. As this book, for me, rewards rereading.

Ok, so….what else? What other treasures did I skim from the top of the chaos of my library?

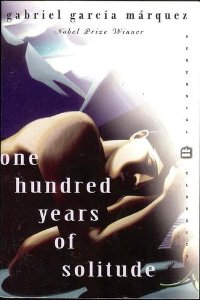

100 Years of Solitude, a book so close to perfect it seems not written but made, something simply plucked, pre-formed, out of the sky.

As a matter of fact, I got a nasty shock reading this Paris Review interview: Marquez talks about writing about Macondo. He talks about it being hard to write about. He writes about different attempts to write this book, none of which were right. I just…..that blew my mind. 100 Year of Solitude was in fact written, and written by a human hand. I know that statement seems hyperbolic, but sometimes when I read this novel, it seems like it must have always existed, timeless, just out of sight.

I wrote about Macondo’s wondrous bookseller here.

His collected short stories also escaped the storage unit.

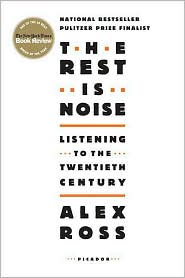

I kept both of Alex Ross’s books close; when writing about music I frequently turn both to The Rest is Noise and Listen to This. Incomparable resources, both, and entertaining, informative and lovingly indulgent. (Wrote briefly about the opening essay of Listen to This here).

A Moveable Feast accompanied me, as well as Hemingway’s collected short stories. I mentioned before that I find companionship and solidarity and comfort from his descriptions of his early writing, before anyone knew who he was besides his wife and Gertrude Stein.

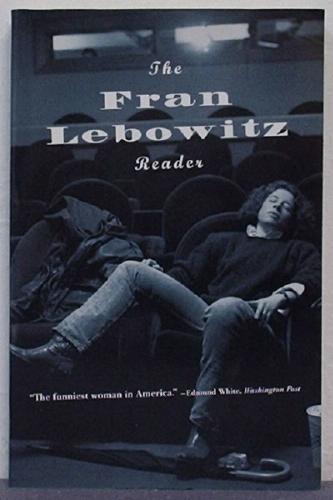

Other than that, I brought home works I find myself dipping in and out of….a lot of short stories, for example. In addition to those of Hemingway and Marquez, I keep close those of Annie Proulx, Colm Toibin, Ann Beattie, DH Lawrence, and Eudora Welty. The poetry of Rilke and Walt Whitman. The Fran Lebowitz Reader, because she will never not be funny, and she’s always there when I start missing New York.

Also, that book has the BEST. COVER PHOTO. EVER.

What books do I regret locking away for a season? What do I keep thinking of ruefully, wishing I had close at hand? Consider the Lobster, the amazing book of essays by David Foster Wallace, and The Giver, which has been one of my favorite books since I was about 8.

A Tale of Two Cities (unaccountably). For Whom the Bell Tolls. Never Let Me Go. No Country for Old Men. Winter’s Bone.

I daydream about being reunited with my library. The day after I move to my next place, I’ll let the clothes sit in the suitcase and leave the cups and saucers wrapped in newspaper. I’ll sit amid towers of alphabetized boxes and pull out each volume and move my hands over the cover. I’ll flip a few pages. I’ll greet each book like an old friend (which each one is). I’ll combine them with the books mentioned above, and the books I’ve acquired since I moved (Oh, how they’ll have to move aside for Infinite Jest).

I think of them, cold in their boxes, waiting for me.

This may sound melodramatic to some, but to others this will make perfect sense: I miss them every day.